Where the grass IS greener.

You must be 21 years of age or older to enter this site. Are you 21 or older?

bud.com helps adults find legal weed near them. We use cookies and similar methods to recognize visitors and remember their preferences, to analyze site traffic, and to measure and improve ad campaign effectiveness. For more info, see our privacy policy.

By tapping 'yes,' you consent to the use of these methods by us and third parties.

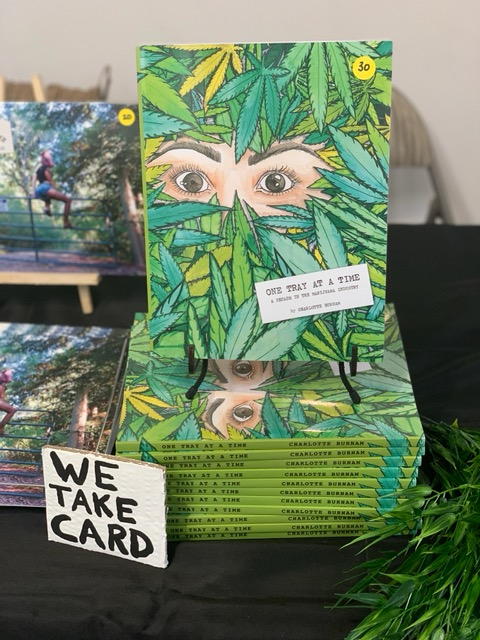

the weed-trimming graphic novel

A new graphic novel by Charlotte Burnam recounts the misadventures of a young woman who spent ten years as a weed trimmer and harvest coordinator on black market farms in Northern California.

by Danielle Simone Brand · December 24, 2018

One Tray at a Time, a new graphic novel by the artist writing as Charlotte Burnam recounts the misadventures of a young woman who spent ten years as a weed trimmer and harvest coordinator on black market farms in Northern California. Drawn with clean lines and peppered with characters such as the hippy couple, “Mandusa” and “Sprinkle Galaxy” who promise to work poorly for a high wage, the graphic novel paints a humorous picture of life on the farms from the perspective of Burnam herself—a Chicago-born, hardworking child of Italian immigrants, whose background in no way prepared her for what she experienced in the Emerald Triangle.

Photo by Xochitl Segura of Charlotte Burnham's One Tray at a Time.

Photo by Xochitl Segura of Charlotte Burnham's One Tray at a Time.

Charlotte Burnam is the pen name of the artist, who includes photos from the grow industry, hand-written grocery lists, journal entries, and other mixed media to flesh out the narrative. Though massive cultural gaps existed between her and the hippies she met on the farms, she ultimately left the industry with a certain affection for the lifestyle, and for the people in it. Burnam spoke with bud.com about her graphic novel and about her insider-outsider perspective on the cannabis industry.

How’s the launch of your graphic novel?

I’ve been having loads of fun with the novel, showing it to people and hearing them laugh. I invited a lot of farmers that I’ve worked with to the book launch.

Everyone has been saying, “That’s so true, that’s hilarious.” I thought some of the people (portrayed) in the book would be upset about it, but they weren’t. They were like, “You nailed it.”

What was the process of writing this graphic novel?

I’ve always been artistic, where I tape things into my journal—bus tickets, articles, doodles, all kinds of stuff like that. I brought new journals to fill up when I moved from Chicago to California in 2008 to work as a trimmer.

It was culture shock for me on the farms—everything was so different—and at that time in northern California there wasn’t good cell phone reception and I didn’t have social media or even a computer. No way to talk to my friends back in Chicago about what I was witnessing. So, this was how I got it down—all the crazy things I was seeing and living.

Photo of Charlotte Burnham by Xochitl Segura.

Photo of Charlotte Burnham by Xochitl Segura.

After working in the industry for about ten years, I realized that my job was becoming obsolete, and my owner was selling the property, so I had to make a plan. I started writing the book and finished it in about five months. It was fast, yes, but I had all the characters and stories in my journal already.

I drew my character specifically for the book, and so I had to face my own issues, like, “What do I look like? How am I representing myself?” I had never drawn myself before because I had always been in my journal doodling about what was going on around me.

Were the über-hippy characters in your book exaggerated?

Everything in the book happened. Like we would hire a caretaker and after a few days he would say, “Oh, I don’t have a driver’s license.” And I was like, “What?! That’s an essential part of the job!”

In Chicago, I worked at a bank for six years. You could be whoever you wanted to be at home, but at work—people came in, and maybe they had the sniffles and you’d be like, “Hey are you OK?” And they’d say, “Sure.”

But in California, if someone had the sniffles and you’d ask if they were OK, they would respond with, “Mercury’s in a really bad place right now, but I feel an overwhelming sense of belonging.”

How do you talk to someone you’re working with about their celestial place in this world? I just wasn’t used to how personal it was.

In the book, you show some of the challenges of being a woman in a male-dominated industry. Can you talk more about that?

Women in the industry have to prove themselves so much more than men. I had to work harder, know more, show up earlier, be the last one to leave the site. If you’re a girl, people will think you’re just sleeping with someone, or you’re just good looking, and that’s why you have this opportunity. And I had to say, “No, I’ve been doing this a long time. I know what I’m doing.”

Once the industry started becoming more mainstream, men were like, “You can work my booth at the conventions.” When I had more experience than them, more knowledge than them, more money than them,they reduced me to the role of being a model because they just needed a pretty face to sell product. I was like, “Are you kidding me? I taught you how to make hash.”

What were the conditions like for you and other workers in the black market?

Work conditions are farm conditions. You’re working in the rain. The roads aren’t regulated, stuff like that. Farms can also be a dangerous place for women because if there is a sexual assault or rape, you can’t report it.

A lot of farms had outdoor showers, so if you were uncomfortable being nude in public—like let’s say that you were some Italian, Catholic immigrant child coming from Chicago to California—and you wanted to take a shower, you would know that seven dudes were about to see you naked. Also, men get up and pee right in front of you.

I was always in fear of being groped, touched, spoken to inappropriately. It happened a lot and there’s no one to talk to about it, no HR department to complain to.

Can you talk more about the theme of not belonging that pops up often in the book?

My parents are Italian immigrants, and they taught me to work really hard. It was important to them that I get a job and a mortgage and a car payment and a marriage and a child. And my friends started having children early, and I always—for some reason—didn’t want to have children. And I think that, right off the bat, for any woman to feel that way is radical.

With immigrant parents who didn’t speak English at home, I didn’t fit in with my friends growing up, either. I was eating different foods, doing different things. When I was with my friends, getting high or getting drunk, or whatever, I would also be in my journals drawing.

In 2008, when my boyfriend at the time asked me if I wanted to move to California, I said, “Yes! Let’s go!” But when I got there, I was like oh my god, what have I done? Go back!

In northern California, I didn’t look like anyone, I didn’t dress like anyone. I felt totally out of my element.

I was also inspired. I saw women who didn’t have children, who ran their own stores, owned art galleries. And I thought, wow.

But right off the bat, no one liked me. I didn’t like Burning Man. I was definitely an outsider in the hippy, weed-growing world.

I think it was my Chicago attitude, mixed with the artsy and creative side, mixed with my fiery female side. It scared a lot of people away from me. I would have a lot of women, especially in northern California, tell me to calm down, to be quiet.

But, not fitting in all those years has also inspired me. In the face of being alone, it made me say to myself, “You can do this, you got this.”

When did you realize that things were changing in the cannabis industry?

In ‘09 or ’10, I started getting concerned about how fast the laws were changing. I witnessed dispensaries opening, being raided, closing, opening again.

I knew right then that it was going to be like alcohol. Weed wasn’t going away, and people were willing to spend money on it. The government was going to sniff that out, find a way to regulate it, control it in a way that was more beneficial to them.

And I knew that when California went recreational, that would be the end of the road. I knew I couldn’t compete with big business. Just like with alcohol (at the end of prohibition), the bootleggers’ work dissipated. And that was going to happen to me.

Photo of Charlotte Burnham by Xochitl Segura.

Photo of Charlotte Burnham by Xochitl Segura.

What do you think about the state of the industry today?

A lot of my friends are dwindling out of farming because of the price of permitting. The price of weed is also dropping dramatically. You can’t compete with the big dogs, because now it’s about quantity—just producing as much weed as possible.

I am proud that social media is bringing women together more. Organizations like Women Grow, Tokeativity, Grow Sisters, and safe spaces for women to get high.

I’m hoping that the safe spaces for women moves across the country, because it shouldn’t just be about fixing our dreadlocks and doing yoga and getting high. Where’s the stuff for my girls working 60 hours a week in Chicago? There are moms working their asses off just to get food on the table and they need to be able to relax and medicate in a safe space, too.

All photos by Xochitl Segura.

Danielle Simone Brand is a writer and a yoga teacher. Her articles and essays about cannabis, parenting, or spirituality (and sometimes all three) appear across the web. She lives in San Diego with her husband and two children.